On any given day, roughly 6 million caretakers and children benefit from The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). The federal assistance program helps pregnant and breastfeeding people, infants, and children under five access healthy food and education. It’s an essential public service that has been shown to reduce infant mortality by 33 percent and help children score higher on the Healthy Eating Index, among other health benefits.

In recent years, WIC has sought to improve participant outcomes through modernization efforts. For example, technological tools could ease the certification process for WIC applicants and participants by offering them more remote options. However, many local and state WIC agencies face barriers to modernization. One of the biggest barriers is the challenge of linking new technology to legacy systems—specifically management information systems (MIS)—that store participant data.

Additionally, many state agencies are part of a consortium that shares an MIS. The MIS documents WIC applicant eligibility, captures and stores participant data, establishes and maintains the authorized WIC product list, and manages benefits packages and Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards through linked EBT systems, and is responsible for issuing benefits for programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Some states have a variation on their consortium MIS, and some states are not part of a consortium and have their own MIS. Moreover, the consortium requires member states to agree on changes to the shared MIS.

We hypothesized that a national API standard for interacting with WIC MIS platforms could improve experiences for WIC participants and staff, and that it could help promote equity by making it easier to scale and reuse tools across state WIC agencies. We wanted to begin testing our hypothesis, so we partnered with Montana WIC on a demonstration project that sought to help us understand the feasibility and value of implementing an API standard in the WIC program in a real world program setting.

-76 percent of surveyed WIC agencies have recently undertaken updating MIS platform technology

-Nearly 6 million people, infants, and children use WIC

From our demonstration project, we began validating our hypothesis and gained deeper insights into how an API standard could benefit WIC participants and staff in this real world program setting. We did this by building an eligibility screener tool and an API prototype that simulated an API being built directly into Montana WIC’s MIS, M-SPIRIT (Montana-SPIRIT). Though we couldn’t actually build an API into M-SPIRIT without updating the MIS, our demonstration project helped us understand the nuances of data transfer with the MIS as well as current policy and business process barriers to implementing APIs and an API standard across MIS platforms.

An API standard can help WIC meet staff and participant needs

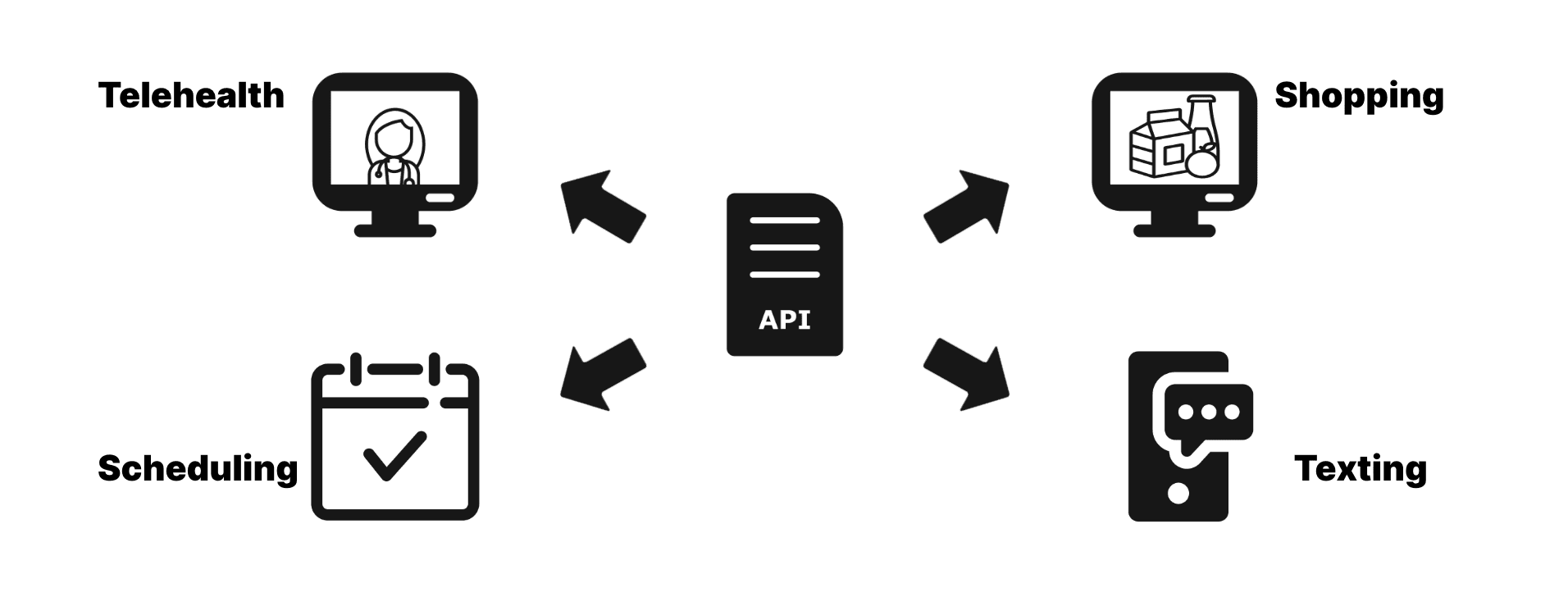

APIs—or Application Programming Interfaces—allow siloed technologies to communicate with one another. To illustrate, imagine you’re ordering a burrito at a restaurant. You tell your order to the cashier who then transfers it to the kitchen. In this metaphor, the cashier is acting as an API by transferring information from one party—you, the customer—to another, the kitchen.

An API standard is a shared, well-defined format for accessing and interacting with data. In the case of the burrito restaurant, there might be signs telling you where to order and employee rules telling the cashier how to send the order to the kitchen. These measures ensure that orders successfully make it from the customer to the kitchen—this is how an API standard functions.

In the context of WIC, APIs can help disparate technologies—such as intake apps, participant portals, or text messaging platforms—communicate with one another and with a WIC state agency’s MIS. This reduces the amount of time WIC staff have to spend on manual data transfer or designing custom integrations that link two systems—a process that’s not repeatable across state agencies. More time freed from administrative burdens for WIC staff means more time spent delivering core services like nutrition counseling.

COVID-era waivers enabled remote service delivery, such as the option for applicants and participants to certify for WIC remotely. This expanded WIC’s impact, according to the National WIC Association and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) recently announced that it will give states the option to maintain these waivers into 2026 because “Initial research suggests that remote services reduced the administrative burdens faced by eligible individuals to accessing and maintaining benefits and that participants were satisfied with remote services.”

We believe an API standard can streamline the implementation, proliferation, and success of modern technology across WIC. An API standard governing how MIS platforms implement APIs would save individual state agencies the time and resources required to design APIs from scratch. It would allow modern technology to be built so that it could be interoperable across MIS platforms, allowing state agencies to easily adopt new technology based on their specific needs rather than going through their consortia to make requests to change the MIS directly.

Our demonstration project in Montana

At the beginning of the project, we sought to understand what it would take to build an API that could eventually contribute to an API standard for eligibility screening data across WIC.

Montana’s consortium uses an MIS called SPIRIT, Montana’s specific version being M-SPIRIT. In order to understand M-SPIRIT, we reviewed key functional documentation and our prior research findings from the WIC landscape assessment. We referenced Montana WIC’s needs assessment to gauge the current state of WIC service delivery, and we interviewed stakeholders to inform our project and our understanding of Montana’s technical capabilities.

We conducted user research to understand the enrollment and certification experience for WIC participants and staff, which allowed us to identify opportunities to improve operations and participant outcomes.

We then collaborated with stakeholders to define a product and technical strategy for delivering a prototype for a participant-facing tool that uses an API. Through conversations with WIC staff, we learned that Montana sought to increase WIC participation among eligible infants and children. They viewed the demonstration project as an opportunity to progress towards this goal while working to overcome systemic barriers to modernization. “Increased participation could occur through an improved referral system to the Montana WIC Program,” the Montana WIC Needs Assessment says. “Funds and staff time should be directed to referral avenues that provide maximum effectiveness.” Montana had no major modernization efforts underway when we began our project, so together, we decided to start small.

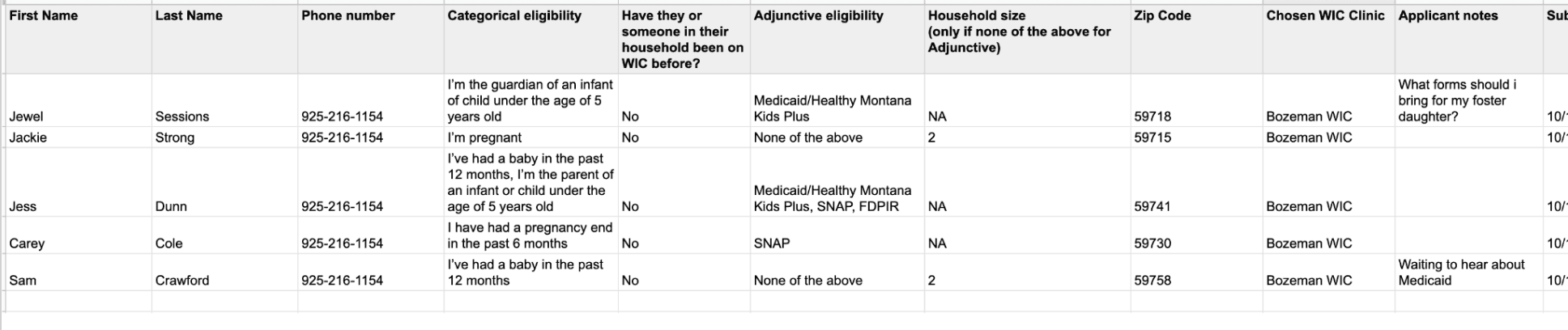

Bearing in mind the results of Montana’s needs assessment, we decided to focus on one immediate program need—increasing WIC participation and outreach—and aligned on prototyping an online eligibility screener. Our screener consisted of a web application with an API that, if fully implemented, could help potentially eligible participants start the process of enrolling in WIC from anywhere, including through community partners or health care providers’ offices.

Currently, WIC applicants in Montana call their local office or go in person to gauge if they are eligible for the program. This puts the burden on the applicant to reach out. Similarly, other screener tools like the FNS screener that Montana participants used in the past put the burden on participants to reach out to WIC staff.

Our screener is designed to use an API to directly transfer applicant data to appropriate clinic staff. Once the eligibility screener we built with Montana is deployed into production, WIC staff will be able to have a more informed conversation with applicants about their eligibility.

It’s important to acknowledge that we did not build an API in production or design a comprehensive WIC API standard. Rather, we delivered a working prototype for an eligibility screener based on our learnings and recommendations. Through this process, we confirmed the value of an API standard and gained knowledge that will inform our ability to recommend an API standard across MIS platforms.

Our work in Montana solidified the need for an API standard

Our demonstration project in Montana solidified our viewpoint that adopting an API standard could improve outcomes for WIC staff and participants. An API standard across MIS platforms would support remote service delivery, it would make data transfer more secure and less burdensome to staff, and it would improve WIC staff workflows.

Recent research suggests that a hybrid delivery model with both remote and in-person options would be effective and well-liked by participants. One recent study found that most WIC participants were satisfied with remote service delivery. Among participants using each method of service delivery, 96 percent reported a high level of satisfaction with phone appointments, 96 percent with interactive texting, 94 percent with online education, 93 percent with email, and 80 percent with video appointments.

Similarly, a research brief from FNS says that “Nearly all State agencies reported that the physical presence and remote benefit issuance waivers ultimately made WIC safer, more accessible, and more convenient for participants’ schedules and a large majority reported that the two waivers improved access to food during the pandemic.”

The option of remote service delivery is especially important in a state like Montana, where WIC participants may live faraway from the nearest clinic. Our interviews with WIC participants in Montana demonstrated a strong desire for hybrid service delivery, and many WIC participants shared that a hybrid model allowed them to miss fewer appointments.

A remote service delivery model would be streamlined by online enrollment and certification tools. Several tools are already used by some WIC state agencies including online pre-applications, participant portals, document uploaders, video conferencing, two-way text communications, and automated chatbots. Though these tools have improved the WIC experience for participants, they largely operate as standalone tools that do not integrate with state MIS platforms. Implementing standalone tools can cause operational burden for WIC staff.

In Montana, we learned that M-SPIRIT only has data import/export functionality related to EBT. As a result, Montana’s IT department created a workaround solution to integrate third party applications that can transfer non-EBT data to M-SPIRIT. However, this workaround solution is brittle, requires substantial manual labor, and is not sustainable since knowledge of the process is lost through staff attrition.

Our demonstration project verified that an API can help states like Montana integrate new tools with their MIS platforms while reducing staff burden. Our screener tool was able to export applicant data to a .csv file that would then be transferred to WIC staff. This data transfer replicated the work of an API.

We considered several options to transfer applicant data to the MIS. We looked into creating a Tableau report to transfer the .csv file to clinic staff, and we considered creating an automated process using powershell scripts and stored procedures to directly insert the data into M-SPIRIT. However, we ultimately decided to email the .csv file to staff. We knew from our research that both email and Excel are known tools for staff and are used in their processes currently.

This option also preserved the MIS as WIC staff’s source of truth on participant data, meaning the organization pulls data from this particular, accurate source to help prevent errors or confusion from multiple data sources. The MIS does not contain any data for pending applications, so injecting information from our screener could disrupt staff workflow. WIC staff said they wanted to establish contact with a prospective participant and validate their eligibility information before entering any data into M-SPIRIT. However, this .csv file became another resource for staff to decipher. Without a move toward interoperability between the MIS and screener tool facilitated by an API, staff can bear the burden of modernization.

More generally, if MIS platforms were able to leverage a standard API, it would be possible to integrate with external tools and platforms without staff needing to decipher multiple sources of data, managing multiple logins, or undergoing additional training.

Implementing an API standard in practice

Based on our research, an API standard would need to check a few boxes in order to support WIC modernization:

Define the data structures, data formats, and critical functions necessary for a WIC program to operate as an API for MIS platforms

Establish a governance structure, governing body, and decision-making framework for ongoing modernization (such a governing body might comprise of FNS, MIS vendor representatives, and state agency stakeholders)

Build out guidelines and provide environments, documentation, and support for developers implementing the new technology

Define versioning and access permissions around the API and its data

Define ways to measure and monitor API adoption

Define a timeline for implementation and deployment supported (and likely funded) by FNS

Though these benchmarks provide guidance on how to begin building an API standard, we acknowledge that there’s much more research to conduct on actual implementation in the WIC space.

If we were continuing this demonstration project, we would first want to outline a practice for data governance. Our work with Montana WIC demonstrated that multiple parties can be responsible for many different data sets. When introducing new tools, we’d want to define who owns and maintains what data and how that data gets managed.

Because our study was limited to Montana, we’d like to validate the screener’s portability by implementing it in another state that uses SPIRIT and eventually with other MIS platforms.

Now is the time for an API standard

We’ve always believed an API standard could modernize and streamline WIC service delivery, and our work in Montana only solidified this viewpoint. During our demonstration project, we observed how APIs can support a hybrid service delivery model while reducing staff burden, ensuring data security, and preserving the MIS as the source of truth. Although some state agencies have implemented custom APIs for their MIS platforms, the effort is not pervasive because it requires funding and a significant time investment from WIC staff.

In addition, piecemeal API implementation misses out on the benefits of a unified API standard, which would unlock interoperability across the entire WIC landscape. FNS has the opportunity to take a leadership role in establishing and incentivizing adoption of an API standard.

And as we wrote last April, an API standard would allow WIC agencies to easily create and adapt new tools without changing their MIS platforms, and it would facilitate states sharing tools with one another, helping WIC agencies meet their specific needs regardless of consortia. An API standard has the potential to eliminate vendor lock-in because vendors could offer products across multiple WIC agencies, independently of the MIS those agencies use.

FNS would also benefit from an API standard because it would be able to leverage resources to scale tools across WIC programs. This would ensure that the best tools get developed, scaled, and used to support a participant-centered program.

Special thanks to Sasha Reid who is serving as a Solutions Architect on this project and contributed to this article.

Written by

Principal Software Engineer

Senior Editorial manager

Director of partnerships and advocacy

Director of product

Principal Designer and Researcher