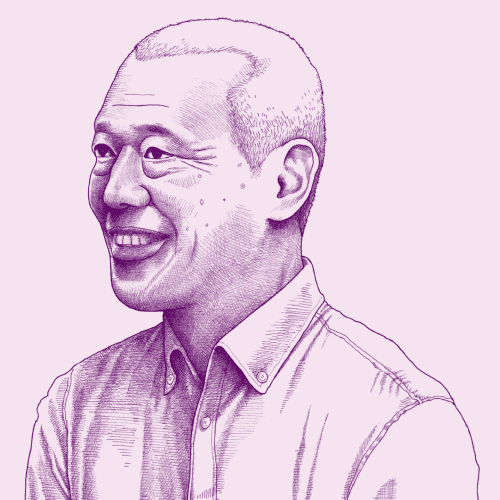

Joanne Woytek, a more than 45-year veteran of The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), is a pioneering trans leader in the federal technology community. Currently, Woytek is the Program Director for the NASA Solutions for Enterprise-Wide Procurement (SEWP) Program, the premier government-wide acquisition contract that provides federal agencies with the latest in internet technology (IT) solutions.

In the mid-’90s, with a 20-year career at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Woytek became the first male-to-female transgender person to transition on the job at NASA — and was one of the first to openly do so in the federal government. After several years of leading support groups and adjusting to a new reality, she focused on her professional career and personal life, and became disconnected from the LGBTQIA+ community.

In recent years, she has become a grandmother and has re-emerged from her “glass closet.” Now, she supports the LGBTQIA+ community through her blog, employee resource group (ERG) leadership, an inclusivity standards committee, and as an active speaker on common issues LGBTQIA+ people face.

Nava’s ERG for people who identify as LGBTQIA+, Kaleidoscope, hosted Woytek in celebration of Pride Month earlier this year. An abridged and edited version of Woytek’s conversation, facilitated by Nava software engineer and co-lead of Kaleidoscope, Michelle Hadfield, is below.

What was it like to transition in the 1990s? How much did you have to figure out on your own?

If you wanted to transition in the 1990s, the “rule” was you had to start a new life — quit your job, your family, and maybe even your city. But I didn’t want to lose everything. I had children and a job I really liked, so I decided to stay. I didn’t do it because I wanted to be a pioneer; I did it because I had to.

There were no workplace protections back then. When I went to legal about my transition, the lawyer told me my employer could fire me at will. So we had to make up the rules as we went along. I was very lucky that I had support from my supervisors, my staff, and co-workers. It wasn’t 100% support, but I was not in the dangerous situation that I know other folks were in.

As an early internet user, I was able to research support groups. I eventually ended up co-leading a Washington D.C. support group and helped start another group in Baltimore. Through these groups, I was able to get the information and support I needed. This was crucial because at that time, it was difficult to find gender-affirming doctors and surgeons.

I wanted to be a leader for the LGBTQIA+ community back then because I saw that people did not always have the support or resources that I had, like a therapist or supportive colleagues. There are risks when you try to be yourself, and I wanted to make sure people understood that as best as they could and help them through that.

How did you balance your career with your transition?

I was very careful because I understood — and was told — that I had no rights. At work, I tried to balance being myself while not speaking out too much. It really came down to having internal support at Goddard — support many people did not have back then. I am the reason for the first all-gender restroom at the Goddard Center, which I did not appreciate enough at the time and really only used the women’s restroom.

What rules did you advocate for in the workplace?

Now, we have a 20+ page manual detailing anti-discrimination policies at NASA — and it’s still a work in progress. There’s a travel policy and general policies to help someone in the workplace who is transitioning. These resources can help someone learn how to change their name, who to notify, how to tell staff members, et cetera. The bottom line in each policy is to be respectful.

What is this concept of the “glass closet” and how did it impact your life?

At one point, I took a break from fully expressing who I was and being an advocate for the queer community. I tuned out what was happening around me by retreating into the glass closet, where everyone could see me and my gender identity, but I was not seeing myself and how I affected others.

I also have this idea of volumes. In the 1990s, I was at a volume nine in my gender expression and identity. In the glass closet, I went down to a volume two. Now, I’m up at a volume 11 and I’m back to being an advocate for the LGBTQIA+ community.

What are you looking for from the larger queer community in terms of support and advocacy?

From my experience co-leading an ERG for the LGBTQIA+ community, I often think about how to reach people who need support. Sometimes we spend so much time tackling the big issues that we forget to support those who really need it. I’m concerned about the people who aren’t part of the community yet, and I want to make sure we make support groups known.

You’ve seen an evolution of acceptance throughout your life. Where would you like to see that acceptance in 10 years from now?

We must learn to accept each other’s differences rather than trying to ignore them. People transition because they need to live as their true selves. If we can get that message out to the world, I think people could become more accepting.

This starts with supporting queer children. Questions about gender identity and expression often don’t start at age 20 or 30; they come up much sooner. Queer children need support from family and professional therapists, but if we take those supports away, their situation with bullying and mental health issues will only worsen.

This has been a heavy conversation, can you tell us a fun memory from your life?

There is a memorable moment I often think about from my transition. I was trying to set my parents up with support before they learned about my transition. So, I went to their conservative parish priest and said “Look, you don’t have to support me, but can you please support my parents because they are not going to accept me.” The priest actually wanted to meet with me several more times. The last time I went as Joanne, and he hugged me and said “You’re the most selfless person I’ve ever known.” At the time, I felt like the most selfish person, because I was transitioning for me. But he understood that I was trying to be conscious of everyone else’s feelings. That was a pretty cool and unexpected moment.